Percussion instruments, though, were only played in connection with Shamanism and Buddhism, the origins of which can be found in Tibetan Lamaism, as well as with the "Tsam dance", which was performed in Mongolia for the first time in the 8th century.

- khuuchir - yoochin - yatga -

Vocal music

- Urtyin duu (long song) - melismatic and richly ornamented, with a slow tempo, long melodic lines, wide intervals and no fixed rhythm.

It is sung in verses, without a regular refrain and with a full voice in the highest register. The melody has a coat, which covers over three octaves. This requires a strict observance of the breathing rules. The breathing is actually free, but the singer has to keep to the strict rules of performance, making only the absolutely necessary breathing breaks without interrupting the melodic ornaments. The richer the voice is and the longer the singer can hold it, the more intensive is the attention paid by the auditors and the more this performance is appreciated.

People usually practise these long songs while being alone in the open steppe and riding along slowly. The repertory is an expression of the liberty and the vastness of the Mongolian steppe and is used to accompany the rites of the seasonal cycles and the ceremonies of everyday life. Long songs are an integral part of the celebrations held in the round tents and they must be sung after the strict rules of performance.

The Mongols don’t use time units to express the time it needs for a certain distance, but they say e.g. that their trip lasted three long songs

There are three categories of long songs

- Bogin duu (short song) - strophic, syllabic, rhythmically tied, sung without ornaments.- Urtyin duu (long song) - melismatic and richly ornamented, with a slow tempo, long melodic lines, wide intervals and no fixed rhythm.

It is sung in verses, without a regular refrain and with a full voice in the highest register. The melody has a coat, which covers over three octaves. This requires a strict observance of the breathing rules. The breathing is actually free, but the singer has to keep to the strict rules of performance, making only the absolutely necessary breathing breaks without interrupting the melodic ornaments. The richer the voice is and the longer the singer can hold it, the more intensive is the attention paid by the auditors and the more this performance is appreciated.

People usually practise these long songs while being alone in the open steppe and riding along slowly. The repertory is an expression of the liberty and the vastness of the Mongolian steppe and is used to accompany the rites of the seasonal cycles and the ceremonies of everyday life. Long songs are an integral part of the celebrations held in the round tents and they must be sung after the strict rules of performance.

The Mongols don’t use time units to express the time it needs for a certain distance, but they say e.g. that their trip lasted three long songs

There are three categories of long songs

| - The extended ones with uninterrupted flowing melodies, richly ornamented, containing long passages in falsetto. | |

| - The usual ones are shorter, less ornamented, and without falsetto. | |

| - The shortened ones have short verses, refrains and melodic courses full of leaps and bounds (Besreg song). |

Short songs are never sung at celebrations, since they are spontaneously improvised and rather satirical. They are often sung in the form of a dialogue and speak of certain friends and incidents, or they are lyrical tales about love, about everyday life and about animals, especially horses.

- Tuuli (heroic-epic myth)

Mongolian epics report about fierce fights between the good end evil powers in a highly qualified literary poetry.

The recital of epics was always bound to rituals, and it was believed to have magical power. The recitation should have a favourable influence on natural spirits, as well as the power to expulse evil spirits. Generally, the epics were sung inside the round felt tents of the shepherds during the period of their search for the winter quarters, before the hunt or a battle, and against infertility or disease.

- Magtaal (praising songs)

Magtaal are sung in honour of the gods of Lamaism and the spirits of nature, heralds or particular animals. Epic texts also contain praise songs for the mountains, the rivers and nature in general. This is an ancient tradition still practised up to date by the tribes in the region of Mongol-Altai in Western Mongolia.

- Khöömij (guttural singing)

The performance of overtone singing takes usually place during social events such as eating or drinking parties.

| The Mongols call their overtone singing höömij (= throat, pharynx). The singer creates a constant pitched fundamental considered as a drone, and at the same time modulates the selected overtones to create a formantic melody from harmonics. | |

| Several techniques are known, depending on the vocal source and the place of resonance: kharkhiraa = lung, khamriin = nose, tövönkhiin = throat and bagalzuuriin = pharynx. Overtone singers form and vary sound and timbre with their mouth, teeth, tongue, throat, nose and lips. They always form two distinct tones simultaneously sustaining the fundamental pitch. | |

| Overtone singing can also be heard from Turkic-speaking tribes in disparate parts of Central Asia. The Bashkir musicians from the Ural Mountains call their style of overtone singing uzlyau; the Khakass call it khai, the Altai call it koomoi and the Tuvinians khoomei. | |

| Up to date, overtone singing is a common feature of Siberian peoples as well as the Kazakhs and Mongolian tribes. Overtone or throat singing is a special technique in which a single vocalist produces two distinct tones simultaneously. One tone is a low, sustained fundamental pitch (a kind of drone) and the second is a series of flutelike harmonics, which resonate high above this drone. Who masters this singing technique may even make the overtone sound louder then the fundamental pitch, so the drone is not audible anymore. A different technique often used by overtone singers combines a normal glottal pitch with the low frequency, pulse-like vibration known as vocal fry. The Turkic tribes in the Altai use to sing their texts in such a low vocal fry register of about 25-20 Hz). |

Dance

- Folk dance

When the Zakhchin and the tribes of Western Mongolia dance their folk dances ("bij" - "bielgee"), they mainly move the upper part of the body. With their movements they express their identity and gender as well as their tribal and ethnic affiliation. Besides the gender-specific movements, there are others that imitate typical activities of their everyday life, such as the nomadic herdsmen's life, the daily work in the fields or the historical events of their tribe. This kind of dance is mainly performed during celebrations inside the ger (round tents), during festivals of the local nobility or during ceremonies in the monasteries.

Every tribe has its particular forms of expression, e.g.:

| - the Dörbed and the Torguts accompany their dances with dance songs; | |

| - the Buryats dance in a circle, always moving in the direction of the sun; a solo singer improvises pairs of verses followed by the chorus singing the refrain; | |

| - the Bayad dance with their knees bent outwards, balancing on them mugs filled with sour mare-milk (airag). | |

| - the Dörbed balance mugs filled with airag on their heads and hands. |

In the past, the mystery dances were of considerable significance in Mongolia. They were always accompanied by music. For these ritual dances the monks wore dance masks made of papier maché. The tsam symbolised the battle of the gods against the enemies. In animism, the oldest form of religious belief (e.g. the Bon-religion), one believes that the whole nature is animated. Human beings and animals are surrounded by good and evil spirits.

|  |  |

| Tshoijoo | Jamsran | Old White Man |

- white old man -

He is the main figure in the tsam mask dance, in which he appears in the role of a clown and dolt.

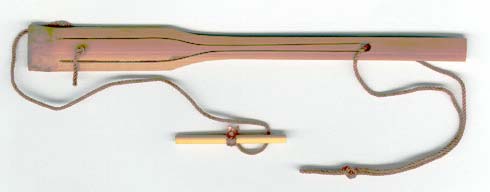

bamboo / wood jews harp

bamboo / wood jews harp

No comments:

Post a Comment